The Origins of the Ethnic Cleansing of the Palestinians, 1880s-1914

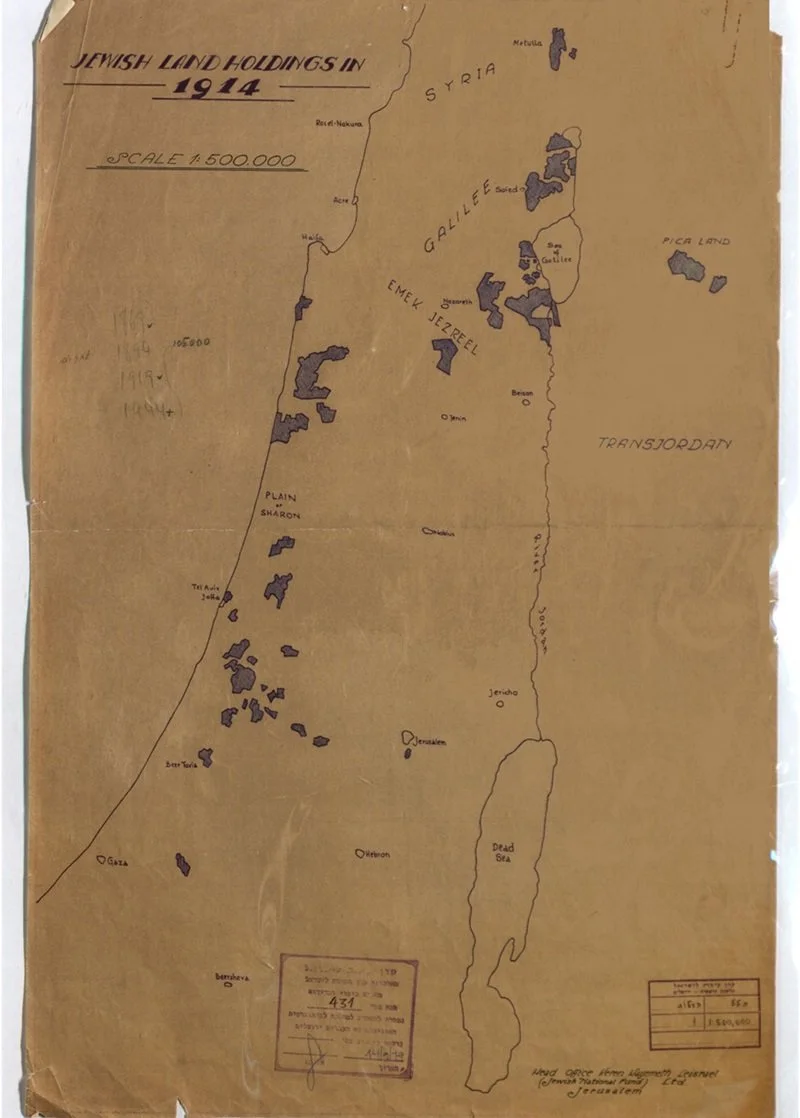

Map of Jewish Settlement in Palestine, 1914. From the KKL-JNF map collection at the Central Zionist Archive. source.

December 22, 2025 — From the 1880s onwards, the Zionist movement set out to buy as much land in Palestine as possible. By 1914, they had secured about 2% of Palestine from absentee landlords, mostly in the coastal plains and the Galilee. At first, they employed the Palestinians and Arabs already living on the land as tenant farmers. But by the early 20th century, the movement believed Jews needed to become farmers themselves to realize the Zionist dream, and so they evicted Arabs and Palestinians instead. This led to violence again and again, and helps explain why many Zionist leaders had settled on “transfer” as the solution to the “Arab problem,” i.e., the problem that there were Arabs in Palestine. This is the origin story of the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians, 1880s-1914.

Late Ottoman Palestine

The story of the Zionist colonization of Palestine began with the 1858 Ottoman Land Code. Prior to its adoption, most Arab farmers in Palestine had lived on communally-owned land in which agricultural plots were redistributed every year or two among village households. But the new Ottoman code privatized land ownership, requiring individuals, rather than groups, to register land. Many farmers either did not understand the land registration process, preferred not to register their land to avoid conscription and overtaxation or were indebted and forced to sell their land. The result was that urban elites bought up large tracts of land in Palestine, employing the Arabs living on it as tenant farmers. By 1918, some 250 families owned over half the land of Palestine (1, 2).

This new system of land ownership, enacted through imperial decree rather than consent of the governed, set the stage for the struggle that would ensue. By 1891, the Zionist movement had established a dozen colonies home to 2,500 settlers. By 1914, that number had reached 58 colonies and 13,000 settlers. By World War I, absentee landlords had sold 2% of the land of Palestine to Zionist institutions. Early stage Ottoman capitalism set the stage for Zionism.

The land sales were fraught with a range of other problems. Absentee landlords sold land that was not theirs to sell, understood as public land, especially grazing pastures (1, 2). The exact boundaries of the land sold was often ambiguous as well. As one historian put it, “the history of Jewish colonization is replete with stories of acts of fraud by sellers, where the naive Jewish buyers bought land without knowing exactly what they had purchased. The result was a chain of claims and counterclaims, violence and counterviolence.” Many of the sales were not officially recorded since it was illegal for Jews to settle in Palestine, as of an 1881 decree, and it was illegal to sell land to Jews in the Jerusalem District, as of an 1892 decree (1, 2)

The Zionist movement was further challenged by the enormous cultural divide between the settlers and the natives they displaced. The Zionists spoke primarily Yiddish, Russian, Polish, German and Ukrainian, they taught not Ottoman Turkish or Arabic but Hebrew in schools and they identified as secular Ashkenazi Jews from Europe. The natives were overwhelmingly Arabic speaking Ottoman Muslim farmers and shepherds from rural Palestine. They shared neither a language, religion, profession or ideology.

Displacement and Violence, 1880-1900

One of the earliest incidents of violence took place in 1883, when a new group of Jewish settlers arrived in the Zionist colony of Petach Tikva, near Jaffa. These settlers wanted to work the land themselves rather than employ Arabs as tenant farmers, as their predecessors had done. The Arab farmers had already completed the first part of a two-year crop cycle, and the dislocation meant they would lose the precious winter cereal crop. This led the Arabs to steal a horse from the Zionists, the Zionists stole donkeys from the Arabs, the Arabs tried to get them back, and realizing they were gone, attacked the Zionists killing one and injuring five.

In 1883, the Zionist colony of Yessud-Hama’ala, established on the western shore of Lake Hula in the Galilee, clashed with the surrounding Arabs as well. The Zubeid Bedouins tried to water their flocks at a pond dug by the settlers, leading to a number of fights. The colony further clashed with the village of Teleil “because of ignorance of Arabic and of the prevailing local customs,” as one historian put it. In one incident, three Arabs rode their horses into the colony and trampled some of the saplings, angering a Zionist gardener, who brawled with the Arabs, killing one of them. The inhabitants of Teleil attacked the colony to avenge their loss, but the Teleil notables intervened and settled the dispute by having two Teleil men appointed as watchmen in the colony.

A similar story unfolded in 1887 when Jewish settlers purchased the Arab village of Qatra from an absentee French owner. The settlers built Gedera next door, occupying most of the agricultural lands of Qatra, although still relying on the village for their water. The settlers broke with local custom and fenced off grazing areas, denying Arab shepherds access. Making matters worse was the “unfair, “arrogant” and “humiliating” treatment displayed towards the native population according to multiple Zionist observers at the time, leading to tension for years. This led to sporadic outbursts of violence, such as one case when a settler was wounded trying to prevent Arab herdsmen from grazing their flocks, or in another, when settlers captured an Arab trying to steal a horse, leading to an Arab night raid on the colony to free the prisoner (1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

These settler-native encounters set the stage for some of the earliest recorded discussions of transfer among Zionist settlers. In 1890, a conversation took place between two settlers in Rehovot shortly after its establishment. “The land in Judea and Galilee is occupied by the Arabs,” one of them said, and so the only option was to “take it from them.” The other settler asked, “how”? “A revolutionary doesn't ask naive questions… It's very simple. We'll harass them until they get out … let them go to Transjordan." That destination became a fixture of the Zionist imagination for decades. Today, that vision has become a reality.

The transfer idea was echoed a few years later in the diary of Theodor Herzl himself, the founder of the Zionist political movement. On 12 June 1895, he famously wrote: “When we occupy the land…we must expropriate gently the private property on the estates assigned to us. We shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries while denying any employment in our own country.” He added that “both the process of expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly.” Herzl understood what had to be done, but also that it had to be done quietly. This became a key principle of the movement, doing Zionism quietly.

It was as if Zionist leaders in Palestine were reading Herzl’s diary entries, as a year later, in 1896, the movement carried out its largest eviction to date, driving out some 600 Druze tenant farmers living in the Galilee village of El Mutallah, on land purchased by Baron Rothschild. The land was sold when most of the men from the village joined Druze rebels in Syria, only to return home to find themselves displaced. The Zionist settlers established the colony of Metulla in its place, leading to years of clashes only brought to an end in 1904 with additional compensation to those uprooted, but not before at least one Zionist settler was killed by the Druze farmers.

In 1896, the Zionist colony of Kastina was established and a land feud immediately broke out between the colony and the Arab village of Hammama. Sheikh Abd el-Hadi of Hammama claimed that the colony occupied Waqf land. Negotiations failed to lead to an agreement, and a local court ruled in favor of the Zionist colony. The next day the sheikh and fifty armed Arabs attacked the colony, and one Palestinian was killed in the ensuing clashes.

The pattern of violence could not be ignored and led Zionist thinkers to think up solutions. In 1898, Nachman Syrkin, a leading Zionist thinker, published a pamphlet calling for an Arab population transfer out of Palestine. "In places where the population is mixed," he wrote, "friendly population transfer and division of territory should ensue. The Jews should receive Palestine, which is very sparsely settled and where the Jews even today comprise ten per cent of the population.” Syrkin was the first to publish a call for the wholesale ethnic cleansing of Palestine (1, 2).

Displacement and Violence, 1900s

These incidents foreshadowed darker days to come. In 1901, the Jewish Colonization Association, founded a decade earlier to buy up land in Palestine for Jewish settlement, set out to remove all the Arab farmers living on land it purchased, including more than 60,000 dunams between Tiberias and Nazareth recently acquired from the Sarsuq family in Beirut. These efforts met with resistance in the villages of al-Shajara, Misha, and Malhamiyya, eventually boiling over into violence. The Zionist land surveyor, Mr. Ossovetsky, was shot at, and troops were brought in to arrest and uproot the tenants. Multiple Jewish settlements were established in their place, and their expansion led to further clashes with Arabs in Lubiyya and Ubeidiyya, resulting in the death of another Jewish settler in 1904 (1, 2).

Chaim Margalit Kalvarisky, a Polish-born agronomist who settled in the Galilee in the 1890s, played a key role in many of the earliest evictions. He recalled having dispossessed the Arabs in Shamsin in order to establish the colony of Yavniel in 1901, describing the reaction of the Bedouins displaced. “They sang songs of mourning for their bad fortune,” adding that the “doleful dirge of the Bedouin men and women…did not stop ringing in my ears for a long time thereafter.”

By the early 20th century, a new ideological wave gained traction among the Zionist settlers. To complement the “conquest of land,” the movement pursued the “conquest of labor.” The goal was to create an exclusively Jewish labor force in the Zionist colonies. Increasingly, Arab laborers working in the Zionist colonies faced harsh treatment, such as in Hadera, where curfews were imposed on Arabs, or in Rehovot, where they were whipped by ha-Shomer guards “in the most trivial circumstances and sometimes without any reason at all, as if they were dogs and not human being,” as one Zionist observed at the time (1, 2).

Increasingly, though, Zionist settlers refused to hire non-Jews at all and sought to expel Arabs already working in Jewish cooperatives. They purged Arabs from the ranks of the settlement guards and watchmen and replaced Arabs with Jews in agricultural jobs and industry (1, 2). Eventually, the goal was to take over every critical sector of Palestine’s economy. All of this further exacerbated the tension caused by Zionist land purchases and settlement expansion.

Displacement, Violence & National Outcry, 1910s

By the 1910s, many Palestinians understood the settlers were part of a movement seeking to establish a Jewish entity or homeland or even a state in a land that was 90% non-Jewish. The Zionist movement in Europe had publicly advocated for a Jewish state in Palestine by the late 1890s and news of its congresses and platforms and statements made its way to Palestine. Increasingly, the evictions were understood not just as settlers displacing natives, but as part of a nation-wide project to uproot Palestinians from their homes and replace them with Jews. Land purchases and displacements thus increasingly took two forms: political violence on the ground and national outcry by the public, as we shall see.

In 1910, the Zionist movement bought a huge swath of land in the Jezreel Valley, between Nazareth and Jenin. The local Ottoman Arab official, Shukri al-Asli, led a popular campaign to compel the government to block the sale. Although the local Arab press supported the campaign, the sale went through anyway. The Palestinian farmers in al-Fula refused to leave and were buttressed by Ottoman soldiers dispatched by al-Asli to confront thirty members of the newly formed Zionist militia, ha-Shomer. In the end, the Governor of Beirut overruled al-‘Asli and evicted the Palestinians. Kibbutz Merhavia was established on the lands of al-Fula, and clashes persisted for years between Merhavia and the displaced Palestinians, who relocated nearby, including one case in May 1911 in which a Ha-Shomer watchman killed a Palestinian near the settlement (1, 2, 3, 4).

In 1913, another incident broke out between the Arabs of Zarnuq and the Jewish colonies southeast of Jaffa. A Zionist guard accused 6 Arabs of stealing grapes in Rishon Le-Zion, the Zionist guard approached the Arabs, the Arabs alleged the guard sought to take their clothes, money, and camels. He reached for his pistol, they attacked him, stole his weapon and ran away. In the ensuing chaos, hundreds of Bedouins and Jewish settlers gathered in what one observer likened to a “battlefield” brawl, leaving an Arab and two Jews dead and multiple injuries.

These incidents were emblematic of the increasingly national character of the struggle: from 1882-1908, 13 Jews were killed by Arabs, only two with a clear national element, according to one historical analysis. But in 1909 alone, though, four Jews were killed for nationalist motives, and between 1909 and 1913 twelve Jewish guards were killed. Put another way, violence directed towards Jews in late Ottoman Palestine was overwhelmingly directed towards armed Zionists watchmen buying up land in Palestine, evicting the Arabs living on it in the pursuit of building an exclusively Jewish entity with an exclusively Jewish labor force in a land of 90% non-Jews.

Conclusion

The Zionist predicament was clear. The goal was to own and cultivate arable land, but as the Zionist thinker Ahad Ha’am put it, “it is difficult to find fields that are not sowed, only sand dunes and stony mountains are not cultivated.” Or, as Israel Zangwill said in New York in 1904, “Palestine proper has already its inhabitants.” Thus, “we must be prepared either to drive out by the sword the tribes in possession as our forefathers did, or to grapple with the problem of a large alien population, mostly Mohammedan.”

This is why the discussions of transfer in the 1890s only grew louder in the 20th century. It’s why Theodor Herzl proposed in his 1901 Draft Charter for Palestine that the Jews would have the right to transfer Arabs from Jaffa to Constantinople, provided they paid their transfer expenses and gave them an equivalent parcel of land at his new destination. It’s why Israel Zangwill broke away from the Zionist movement, at least temporarily, establishing the Jewish Territorial Organisation to build a Jewish homeland outside of Palestine, given that it was already inhabited (1, 2). It’s why, in 1911, the head of the Zionist Office in Palestine, Arthur Ruppin proposed “a limited population transfer" of the Arab peasants from Palestine to the northern Syrian districts of Aleppo and Homs,” repeating his proposal in another letter in 1914. And it’s why, in May 1912, the German Zionist leader Leo Motzkin explained that “around Palestine there are extensive areas. It will be easy for the Arabs to settle there with the money that they will receive from the Jews." And it’s why he said that “one of our most difficult tasks will be to accustom the Arabs to the thought that Palestine is a Jewish land - Eretz Israel” (1, 2).

When Jewish settlers bought land in Palestine, usually from absentee landlords, they denied Arabs access to grazing pastures and agricultural land, often mistreating them in the process, usually leading to clashes. By World War I, the colonies southeast of Jaffa clashed with Zarnuqa, Petah Tikva with Yahudiya, Kefar-Saba with Qalqilya, Sejera with el-Sejera, Tur’an, Kafer-Kanna, Kafer-Sabet and Yessud-Hama’ala with Teleil, Yavniel with Shamsin, Gedera with Qatra, Merhavia with al-Fula and El Mutallah with Metulla. Thousands of Palestinians and Arabs had been uprooted and two dozen Jews and Arabs had been killed in the process.

There is a tendency to believe the history of the Palestine question is complex and controversial, but there isn’t that much controversy in the actual history. Scholars do not debate the reasons for the violence between Zionist settlers and Palestinians. The pattern of Jewish settlement, Arab displacement and violence is well documented, both by anti-Zionist historians and Zionist apologists. This pattern was “repeated in most of the moshavot during the early decade,” as Benny Morris put it, adding that “many of the villagers continued to nurture a deep, lasting resentment toward the newcomers” as a result. Or as Neville Mandel wrote, “there was scarcely a Jewish colony which did not come into conflict at some time with its Arab neighbours, and more often than not a land dispute of one form or another lay behind the graver collisions.”

If you enjoyed this article, check out our online courses on the history of Palestine and Israel, Zionism, the Palestinians and Jewish anti-Zionism.

Subscribe to the Palestine Nexus Newsletter: